Tetanus (Lockjaw): Causes, Symptoms, Treatment, and Prevention

- August 26, 2025

- 1 Like

- 156 Views

- 0 Comments

Overview

Tetanus, often called lockjaw, is a life-threatening disease of the nervous system caused by the bacterium Clostridium tetani. These bacteria live in soil, dust, and animal waste, and their spores can survive for years even in harsh environments. Once the spores enter the body through a wound, they release a powerful toxin known as tetanospasmin, one of the most dangerous toxins in existence. This toxin interferes with nerve signals, causing uncontrollable muscle stiffness and spasms.

Although tetanus is now rare in developed countries thanks to widespread vaccination, it continues to be a serious public health concern in parts of Africa and Asia where vaccination rates remain low. Globally, it is still responsible for thousands of deaths every year, particularly in newborns and mothers who lack access to immunization and safe birthing practices.

Causes and Transmission

Tetanus is not contagious — you cannot catch it from another person. Instead, infection occurs when C. tetani spores enter the body through cuts, puncture wounds, burns, or even small scratches that go unnoticed. The spores thrive in deep, oxygen-poor wounds, where they become active and release their toxin.

While many people associate tetanus with stepping on a rusty nail, the rust itself is not the cause. Rusty tools and old farm equipment are often found in soil-rich environments where C. tetani lives, which explains the link. Other potential causes include animal bites, contaminated surgical tools, unsterile needles, insect bites, frostbite, and burns.

Certain groups face higher risk, including people over 65 (who may not be up to date with boosters), individuals with diabetes or weakened immune systems, and those who inject drugs. Neonatal tetanus, a severe form of the disease, can affect babies born to unvaccinated mothers if the umbilical cord is cut with contaminated instruments.

Symptoms and Progression

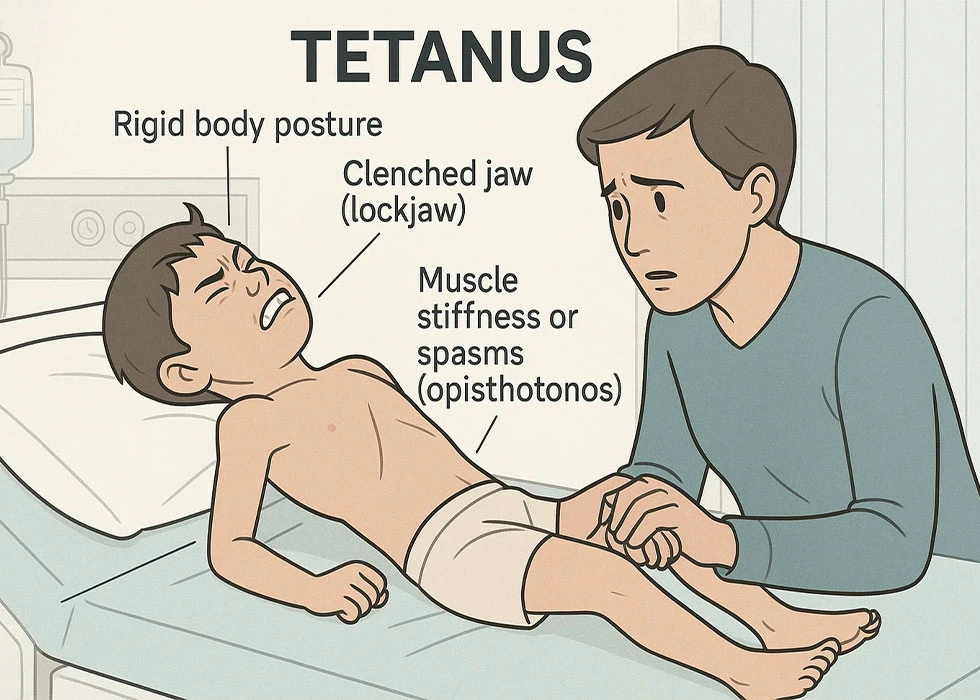

The incubation period for tetanus ranges from three to twenty-one days, with an average of about ten days. The first sign is usually stiffness in the jaw muscles, leading to the well-known symptom of lockjaw. From there, the stiffness spreads downward to the neck, chest, abdomen, and limbs.

Early symptoms can resemble the flu, including fever, headache, fatigue, and difficulty swallowing. As the disease progresses, muscle spasms become increasingly severe and can be triggered by even minor stimuli such as noise, light, or touch. These spasms may arch the back, stiffen the legs, and cause fists to clench. Breathing difficulties are common when chest and throat muscles are affected.

Other possible symptoms include seizures, drooling, rapid heartbeat, excessive sweating, high or low blood pressure, and persistent painful rigidity. In the most severe cases, complications like aspiration pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, fractures, or cardiac arrest may occur.

There are four main types of tetanus:

- Generalized tetanus, the most common form, where spasms spread throughout the body.

- Localized tetanus, with muscle spasms near the wound.

- Cephalic tetanus, which follows a head injury and affects cranial nerves.

- Neonatal tetanus, which affects newborns and is almost always fatal without treatment.

Complications

Tetanus can be devastating if untreated. The constant spasms and muscle rigidity may lead to broken bones, respiratory failure, or blockages in the lungs due to blood clots or aspiration. Pneumonia and kidney failure are also common complications. Even with modern intensive care, the disease carries a significant risk of death. Survivors may face a long recovery period, sometimes with lingering nerve and muscle problems.

Diagnosis

There is no single lab test to confirm tetanus. Instead, doctors rely on medical history, wound history, and clinical symptoms such as jaw stiffness, painful spasms, and difficulty swallowing. A “spatula test” may sometimes be used, where touching the back of the throat with a soft instrument trigger an involuntary jaw spasm rather than a gag reflex, suggesting tetanus.

Because tetanus symptoms can resemble other diseases, such as meningitis or seizures, careful evaluation is important. However, if tetanus is suspected, treatment usually begins immediately without waiting for further confirmation.

Treatment

There is no cure for tetanus once the toxin has affected the nervous system. Treatment instead focuses on neutralizing the toxin, controlling symptoms, and supporting the body until the toxin’s effects wear off. Most patients require hospitalization, often in an intensive care unit.

Treatment typically includes:

- Tetanus immune globulin (TIG): An injection that provides immediate antibodies to neutralize circulating toxin.

- Wound care: Cleaning and debriding the wound to stop further toxin production.

- Antibiotics: Such as metronidazole, to kill remaining bacteria.

- Muscle relaxants and sedatives: To control spasms and seizures.

- Breathing support: Severe cases may require intubation and mechanical ventilation.

- General supportive care: Fluids, pain relief, and management of blood pressure or heart complications.

Recovery can take weeks to months, as the body must regenerate new nerve endings unaffected by the toxin.

Prevention

Tetanus is one of the most preventable infectious diseases. The cornerstone of prevention is vaccination.

- Childhood immunization: Children receive the DTaP vaccine (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis) in a series of doses between 2 months and 6 years of age.

- Adolescents and adults: A booster (Tdap or Td) is recommended at age 11–12, with repeat boosters every 10 years throughout adulthood.

- Pregnancy: A booster is advised during the third trimester to protect both mother and newborn.

- After injuries: If someone sustains a contaminated wound and their last booster was more than 5 years ago, another dose may be required.

Additional preventive measures include cleaning all wounds thoroughly, seeking prompt medical care for deep or dirty wounds, avoiding unsterile needles, and ensuring safe childbirth practices in areas where neonatal tetanus is a risk.

Outlook

With early and appropriate medical care, the outlook for tetanus has improved significantly in recent decades. However, even with treatment, tetanus can still be fatal in 10%–20% of cases. In resource-limited regions, the death rate may be far higher. Survivors often need months of rehabilitation, but they do not develop lifelong immunity, meaning vaccination remains necessary to prevent future infections.

Conclusion

Tetanus remains one of the most feared but preventable infections. While cases have become rare in developed countries thanks to vaccination, it continues to threaten unvaccinated individuals worldwide, particularly in developing regions. Lockjaw and muscle spasms are hallmark signs that require immediate emergency care. With continued global vaccination efforts, neonatal tetanus cases have dropped significantly, but complete eradication requires ongoing commitment to immunization and wound care awareness.

Leave Your Comment