Ebola Virus Disease (EVD): Symptoms, Transmission, Treatment & Prevention

- August 22, 2025

- 1 Like

- 96 Views

- 0 Comments

Overview

Ebola virus disease (EVD), formerly known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, is a rare but life-threatening infection caused by several species of the Orthoebolavirus genus. The disease first appeared in 1976 during outbreaks in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo, near the Ebola River, which gave the virus its name.

Ebola is considered one of the deadliest viral hemorrhagic fevers, with past outbreaks showing fatality rates ranging from 25% to 90%. On average, about half of people infected during outbreaks do not survive. The disease damages the body’s blood vessels, weakens the immune system, and can cause severe bleeding and organ failure. While rare, Ebola outbreaks remain a major public health concern, especially in Central and West Africa.

What Is Ebola Virus?

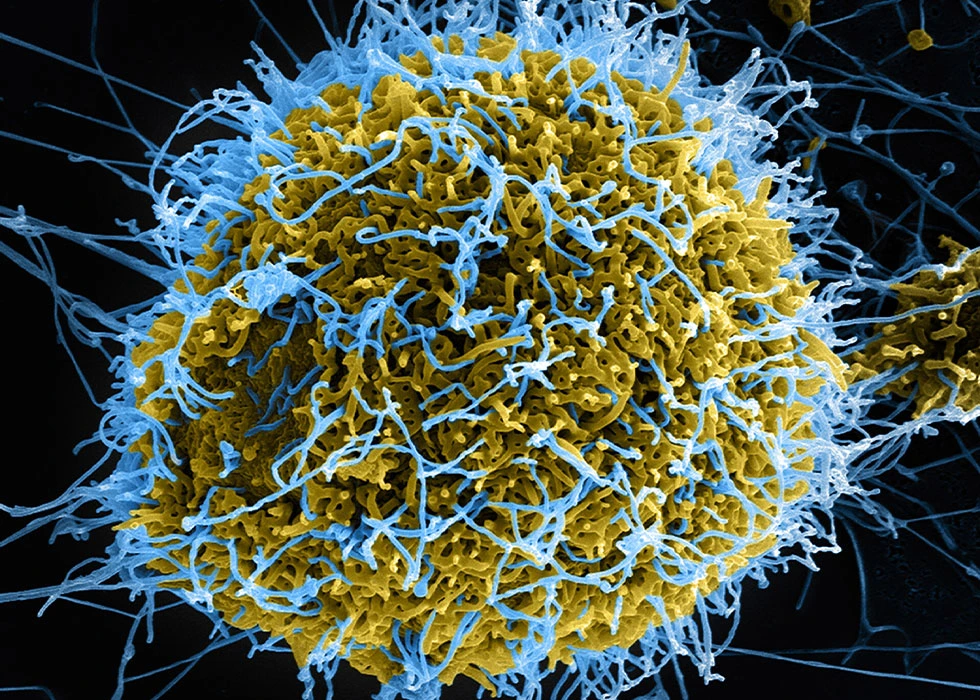

Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) is caused by viruses in the Filoviridae family, which appear as long filament-shaped particles under a microscope. These viruses carry single-stranded RNA and cannot reproduce on their own, so they invade host cells to multiply. Once inside, they spread quickly, causing damage to organs and the immune system.

There are five known species of Ebola virus:

- Zaire ebolavirus (Ebola virus) – the most common cause of outbreaks and the deadliest strain.

- Sudan ebolavirus (Sudan virus) – responsible for several large outbreaks, with fatality rates around 50%.

- Bundibugyo ebolavirus (Bundibugyo virus) – linked to outbreaks in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

- Taï Forest ebolavirus (Taï Forest virus) – extremely rare, identified in a single human case in Côte d’Ivoire.

- Reston ebolavirus (Reston virus) – found in primates and pigs in Asia; it can infect humans but has never caused illness in people.

Two additional related viruses exist: Marburg virus, which also causes hemorrhagic fever in humans, and Bombali virus, discovered in bats but not known to infect people.

How Does Ebola Spread?

Ebola is not airborne like influenza or measles. Instead, it spreads through direct contact with:

- Blood or body fluids (such as urine, stool, sweat, saliva, vomit, breast milk, or semen) of an infected person.

- Contaminated objects like bedding, needles, or medical equipment.

- Infected animals such as fruit bats, monkeys, chimpanzees, or antelope, often through hunting, butchering, or preparing bushmeat.

Human-to-human transmission occurs only once a person is showing symptoms, but the virus can linger in certain body fluids. Ebola has been found in semen for months after recovery, meaning survivors can still transmit the disease sexually. Pregnant women who contract Ebola may also pass it to their fetus during pregnancy or childbirth.

Importantly, Ebola is not spread by mosquitoes, water, or casual contact, and airborne spread has never been documented.

Symptoms of Ebola Virus Disease

Ebola symptoms usually appear between 2 to 21 days after exposure. The illness often begins like the flu, but can escalate into life-threatening complications.

Early symptoms may include:

- Sudden fever and chills

- Severe headache

- Muscle and joint pain

- Sore throat and weakness

- Loss of appetite and fatigue

As the disease progresses, more severe signs may develop:

- Vomiting and diarrhea, sometimes bloody

- Rash and red eyes

- Stomach pain and cramping

- Unexplained bleeding or bruising (from gums, nose, stool, or vomit)

- Black, tarry stool or bloodshot eyes

- Confusion, seizures, or neurological problems in advanced stages

In the most critical cases, Ebola leads to shock, multiple organ failure, brain inflammation, and death.

Complications and Long-Term Effects

Ebola can be fatal within days to weeks if not treated promptly. Survivors may experience long-lasting health problems known as post-Ebola syndrome, including:

- Eye pain, inflammation, or vision loss

- Joint and muscle pain

- Severe fatigue and headaches

- Memory problems and nerve pain

- Hearing issues

- Weight loss, abdominal pain, or skin problems

The virus may persist in certain areas of the body, such as the eyes, central nervous system, and semen, even after recovery.

Diagnosis

Because Ebola symptoms resemble other tropical illnesses like malaria, typhoid fever, and yellow fever, laboratory testing is essential for diagnosis. Doctors use:

- PCR tests (Polymerase Chain Reaction): to detect viral genetic material.

- Antibody tests (ELISA): to check if the immune system has produced a response.

- Blood counts: to monitor white blood cells and platelets, which often drop during Ebola infection.

Early diagnosis is critical for improving survival and preventing further spread. Patients suspected of having Ebola are isolated immediately until test results are confirmed.

Treatment Options

There is still no universal cure for Ebola, but advances in treatment have improved survival rates.

Approved therapies include:

- Inmazeb® – a combination of three monoclonal antibodies.

- Ebanga® – a single monoclonal antibody drug.

Both target the Zaire strain of Ebola and are administered through intravenous infusion.

Supportive care remains essential and includes:

- IV fluids and electrolytes to prevent dehydration.

- Oxygen therapy for breathing problems.

- Pain relievers and medications for fever, vomiting, or diarrhea.

- Blood transfusions if necessary.

- Treating any secondary infections.

Prompt medical care significantly increases the chance of survival.

Vaccines

Vaccination is a key breakthrough in preventing Ebola outbreaks.

- Ervebo® vaccine – approved by the FDA and WHO, protects against the Zaire strain of Ebola. It has been used in outbreak settings with strong effectiveness.

- Zabdeno® and Mvabea® vaccines – given in two doses, approved by the European Medicines Agency for adults and children over one year old.

These vaccines are mainly recommended for people at high risk, such as healthcare workers, laboratory staff, or those living in areas with active outbreaks.

Prevention

Even with vaccines, preventing Ebola requires strong infection-control practices. Important measures include:

- Avoid contact with blood or body fluids of infected people or animals.

- Wear protective equipment (masks, gloves, gowns, goggles) when caring for Ebola patients.

- Avoid traditional burial practices that involve touching infected bodies.

- Do not eat bushmeat from wild animals like bats, monkeys, or antelope.

- Wash hands frequently with soap and disinfect contaminated surfaces.

- For survivors, practice safe sex (condoms) until medical testing confirms the virus is no longer present in semen.

History of Ebola Outbreaks

Since its discovery in 1976, Ebola has caused multiple outbreaks in Africa, with varying severity.

- 1976 (Zaire and Sudan): First recorded outbreaks; death rates up to 88%.

- 1995 (DR Congo, Kikwit): Over 300 cases, 250 deaths.

- 2014–2016 (West Africa): The largest outbreak in history, affecting Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone with 28,652 cases and 11,325 deaths. Small numbers of cases also appeared in the U.S. and Europe.

- 2018–2020 (DR Congo): The second largest outbreak with nearly 3,500 cases and over 2,000 deaths.

While outbreaks have declined in recent years, Ebola remains a public health threat. Ongoing monitoring, rapid response, and vaccination campaigns are critical to preventing future crises.

Outlook and Prognosis

Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) remains one of the world’s most dangerous viruses, but survival rates are improving thanks to modern treatments, supportive care, and vaccines. With early diagnosis, patients have a significantly higher chance of recovery. Survivors typically develop antibodies that provide immunity for at least 10 years, though they may still face long-term health complications.

The risk of a global Ebola pandemic is considered low, since the virus spreads mainly through direct contact rather than airborne transmission. However, continued vigilance is needed, particularly in Africa where Ebola reservoirs like fruit bats are found.

Leave Your Comment